Dr. Sam Umland is the former Chair of the English Department at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, where he taught film and literature for thirty-four years. He is the author of Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations (Greenwood, 1995), and with his wife, Dr. Rebecca Umland, he co-authored The Use of Arthurian Legend in Hollywood Film (Greenwood, 1996), and Donald Cammell: A Life on the Wild Side (Fab Press, 2006). In addition, Dr. Umland has authored The Tim Burton Encyclopedia (Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), as well as dozens of book chapters, articles, and reviews. His monograph on The Man Who Fell to Earth was published by Arrow Books in 2018.

Dr. Umland was kind enough to let me interview him about Donald Cammell, Performance, and the films Cammell made after Performance was released. This is the first half of a two-part interview.

JF: Now that Performance has been given a 4K Blu-ray release by Criterion, what do you hope viewers take away from seeing the film in 2025?

SU: Admirers of the film will welcome Criterion’s release 4K UHD release, which also has the original UK version soundtrack. If some viewers haven’t yet seen the film, this certainly will be the way to see it.

I should mention that previously, in 2017, Warner Brothers issued in the UK a Blu-ray/DVD release of Performance as an hmv.com exclusive as part of its “Premium Collection” series. The Blu-ray transfer on that package is beautiful, I mean fabulous, and it, too, has the original UK soundtrack. It also contains the “Influence and Controversy” documentary from 2007 included on the Criterion release, the original trailer, and the “Memo From Turner” promotional short as well, emphasizing (perhaps over emphasizing) Mick Jagger’s participation in the film.

Happily, the Criterion release includes Kevin Macdonald and Chris Rodley’s 1998 documentary, Donald Cammell: The Ultimate Performance. This documentary had previously been available only on Arrow Films’ Blu-ray release of Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye, a release on which I was heavily involved, and for which I provided the audio commentary. Those interested in Performance will find the documentary on Donald Cammell quite interesting, despite the fact that it perpetuates fallacious myths (for instance, the “he lingered for 45 minutes after shooting himself in the head” nonsense).

There is one thing to be aware of, though, the cut we now have of Performance, the version as it currently exists on the Warner Brothers Blu-rays and appearing on the Criterion 4K release, is not Donald Cammell’s final cut, the version he and Frank Mazzola re-edited for production head John Calley at Warner Brothers in 1970.

Frank told me many times that the existing cut has pieces missing, and David Cammell told me the same thing.

As Rebecca and I indicate in our book, 2 minutes and 45 seconds are missing from the cut John Calley approved. Apparently, these additional cuts were demanded by then Warner Brothers president Ted Ashley.

Frank Mazzola told me before he passed away that this cut footage still exists in the Warner vaults, and he knew how and where to track it down.

I thought perhaps a Criterion release of Performance might enable a long overdue restoration of these cuts, but that didn’t happen; apparently it was not something Criterion was interested in pursuing. Alas, Frank Mazzola is no longer with us to help with any such restoration, so that opportunity now seems permanently lost.

JF: How did you first get interested in director Donald Cammell and Performance?

SU: I had the Performance soundtrack before I ever saw the movie. When I was in high school, Warner Brothers Records started issuing LPs at bargain prices that were promotional “samplers,” consisting of various tracks from current or forthcoming Warner Brothers rock/pop releases. The idea was that if a listener liked a particular song, he would be compelled to buy the album from which the song came. One of the many samplers I bought contained a track from Performance called the Harry Flowers theme. The track was an instrumental, not rock music at all, closer to “muzak,” but I thought it was an unusual track to include on the sampler. That’s how I first discovered Performance, through the music.

I didn’t actually see the film until I was a college student a few years later. It goes without saying that I’d never seen anything remotely like it before. A cliché, but true.

For me, Performance was like a revelation, a “Satori” or sudden awakening, a demonstration of what the cinema could do, what it could be, its potential. It stayed in my head long after I’d seen it.

My interest in Donald Cammell himself came later, after I saw Demon Seed in 1977. I think Demon Seed is a great film, too, with lots of wonderful moments and fleeting images, and I suspect more popular with audiences now than Performance.

I didn’t know anything about Donald Cammell, of course. At that point, he was a sort of elusive figure, which only contributed to his mysterious “aura.”

JF: One part of Performance that’s seldom discussed is the soundtrack, which is really great. How did that all come together? Didn’t Cammell originally want The Rolling Stones to write and perform all the music?

SU: Yes, it is a great soundtrack, the first genuine rock ‘n’ roll score, because it is not a compilation of songs or singles from the movie but is comprised of music written specifically for the film. Well, with the exception of The Last Poets, which Cammell insisted on using.

In addition, there are some interesting, uncommon instruments used in the music, not what you would have heard on a soundtrack at the time. I’m not simply referring to the use of the Moog synthesizer, either.

To my knowledge, Donald Cammell never wanted the Rolling Stones to write and perform the music for Performance. Mick Jagger was friends with Jack Nitzsche and he recommended Nitzsche to Cammell. Nitzsche had worked with Jagger on some early Sixties Rolling Stones records, and had arranged “You Can’t Always Get Want You Want.”

Donald loved Nitzsche’s method of working which favored innovation and experimentation.

The music for Performance was recorded in Los Angeles, where Nitzsche was assisted by Russ Titelman, who along with Ry Cooder and Randy Newman had previously worked on Nitzsche’s rejected score for Candy (1968). Additional musicians included Merry Clayton, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Gene Parsons, and Bernie Krause. Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause were the masters of the Moog synthesizer at the time.

Incidentally, Performance is the first movie to feature the Moog synthesizer as a prop.

JF: Why do you think so many people today, especially young people, are unfamiliar with Performance and haven’t seen the film?

SU: I was a film studies student in college in the early to mid-Seventies when that field of study was just beginning to take hold in U.S. colleges and universities. Films like Performance were shown as part of the required course viewing, mine anyway. Not so anymore, at least, I strongly suspect not.

I’m not certain, but young people in the UK may know something about Performance because it’s a British film featuring a largely British cast.

Of course, Mick Jagger is now an elderly grandfather—actually, a great grandfather—no longer a youthful image of rebellion or a demonic version of the outlaw hero. Mick Jagger never had much of an acting career and was never a genuine movie star, so I suspect his star billing in a movie from half a century ago doesn’t carry much clout with young people now, no more than, say, Elvis Presley.

JF: Performance was Donald Cammell’s first film as a director (or co-director in this case). How did he come up with the idea?

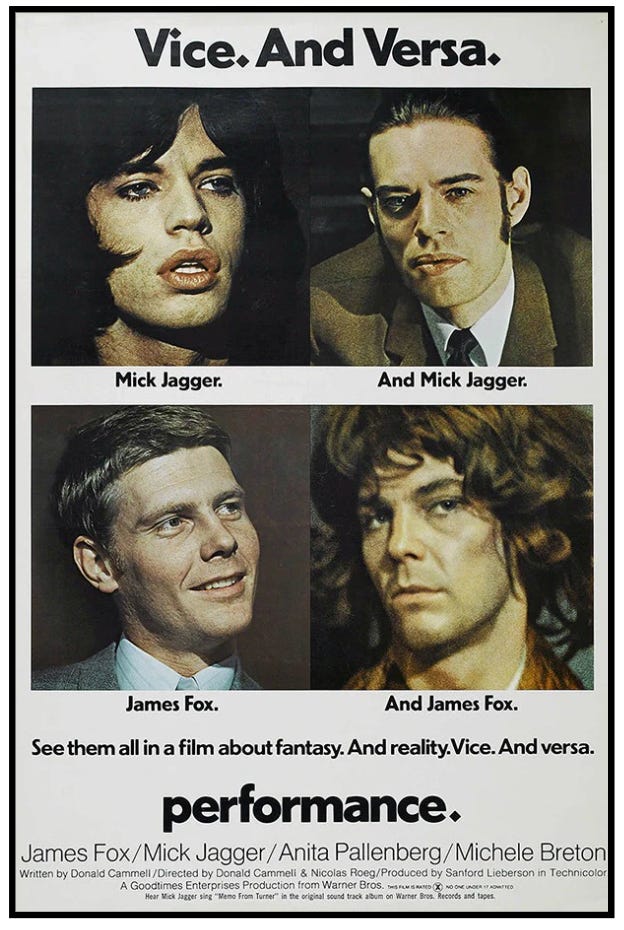

SU: It was Donald Cammell and producer Sandy Lieberson’s joint idea, really. The idea was to pair two famous rebel heroes, Marlon Brando and Mick Jagger. Of course, a film starring Brando was never going to happen, but that was how it started.

JF: How did Cammell’s friendship with Anita Pallenberg and The Rolling Stones affect the way he developed the film?

SU: Donald Cammell said that he was never really a part of the Sixties “Swinging London” scene, and that’s true, he wasn’t. After a short period of living in New York City in the early Sixties and a couple of failed gallery exhibitions of his paintings—he trained at the British Royal Academy of Art, he moved to Paris with his then girlfriend, Deborah Dixon, who was a fashion model.

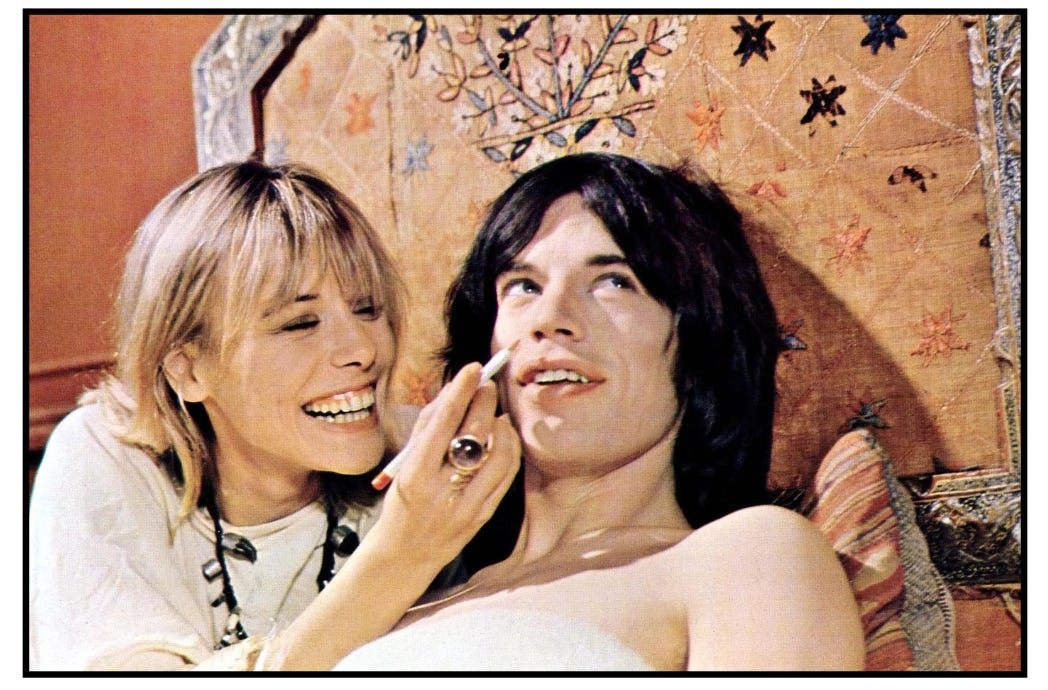

It was in Paris that he met Anita Pallenberg, who at the time was also working as a model. While he spent much of his life in the United States, he liked to consider himself a citizen of France.

In any case, he didn’t meet the Rolling Stones until a show at the Paris Olympia in April 1965. He was intrigued by the Stones due to their “pop star” status, and he and Brian Jones “hit it off” as the saying goes. But certainly, no movie deal was ever discussed or even imagined at the time.

Only later, long after the Performance years, did Cammell acknowledge Anita Pallenberg’s contribution to Performance.

She told me during my interview with her that she, Donald, and Deborah worked on Performance while sitting on the Saint-Tropez beach, remembering one day when a sudden gust of wind blew the completed pages into the water, and they had to retrieve them and quickly dry them off with an iron.

Even if you suspect her memories have been distorted by time, Donald Cammell himself said she helped him immensely with conceptualizing Performance.

I accept this as true, because on several occasions Cammell admitted he was only distantly connected to the Sixties British rock music scene.

For instance, it was his brother David Cammell, an enterprising producer, who arranged for Performance to use the Beatles’ Moog synthesizer, and it was David who arranged for the use of John Lennon’s white Rolls Royce at the film’s conclusion. Well, to be strictly accurate, while John Lennon and Yoko Ono were often seen in that white Roller, it actually belonged to Apple Corps.

Anyway, the Chelsea of 1950s London, where Donald Cammell the painter had his studio, was much different by the late Sixties when he returned to London to make Performance.

JF: How would you summarize the film for those who haven’t seen it?

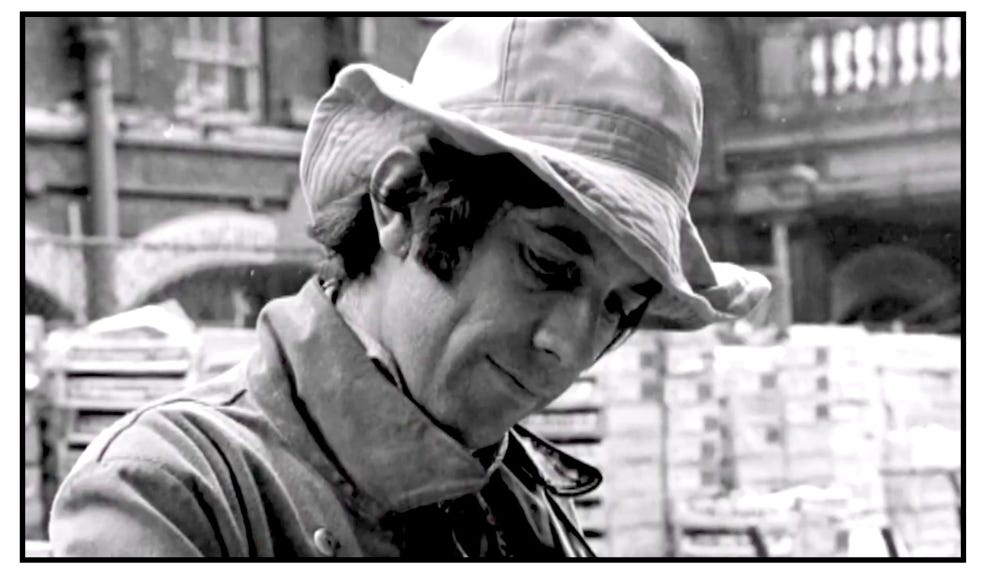

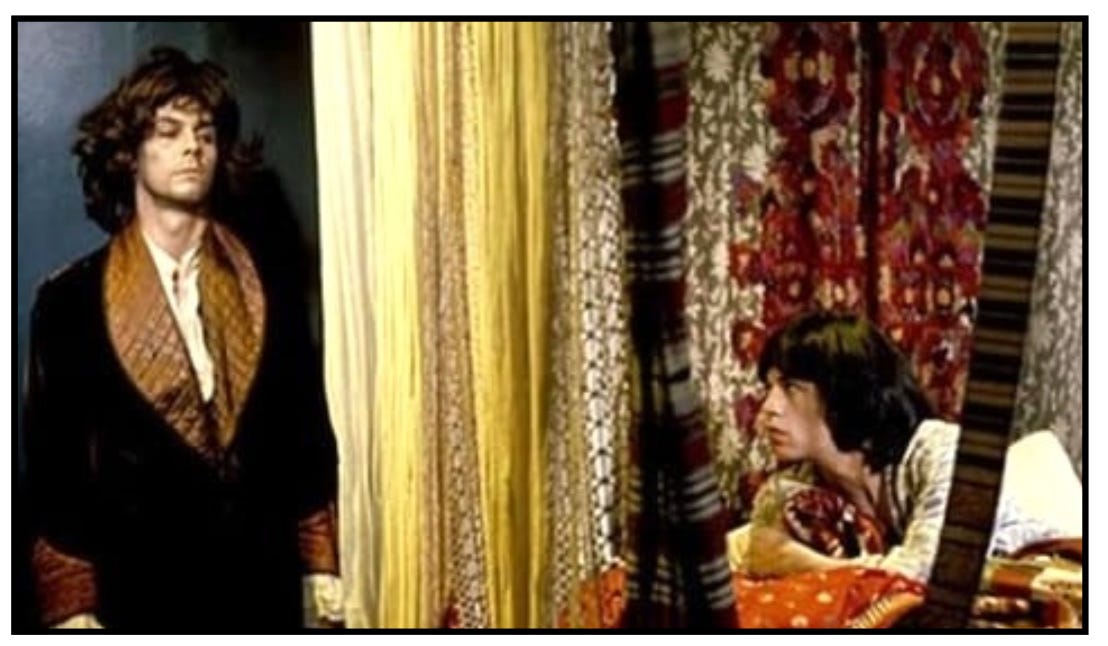

SU: A London gangster seeking to escape his certain execution takes refuge in a house where a reclusive pop idol, his star having begun to fall, is living in a ménage à trois with two women. That is the broad plot outline, and it admittedly tells us nothing about the movie.

JF: What do you think makes Performance so unique?

SU: Performance is a paradox, at once very realistic and very stylized. A gangster on the lam was hardly a new plot idea when Performance was made, but as we watch it, it is as if we are seeing the story for the first time. Chas is hardly a stereotypical jack the lad (as Harry Flowers would say), but moody and irascible. Like Chas, the movie shifts moods unpredictably, keeping the viewer off-kilter.

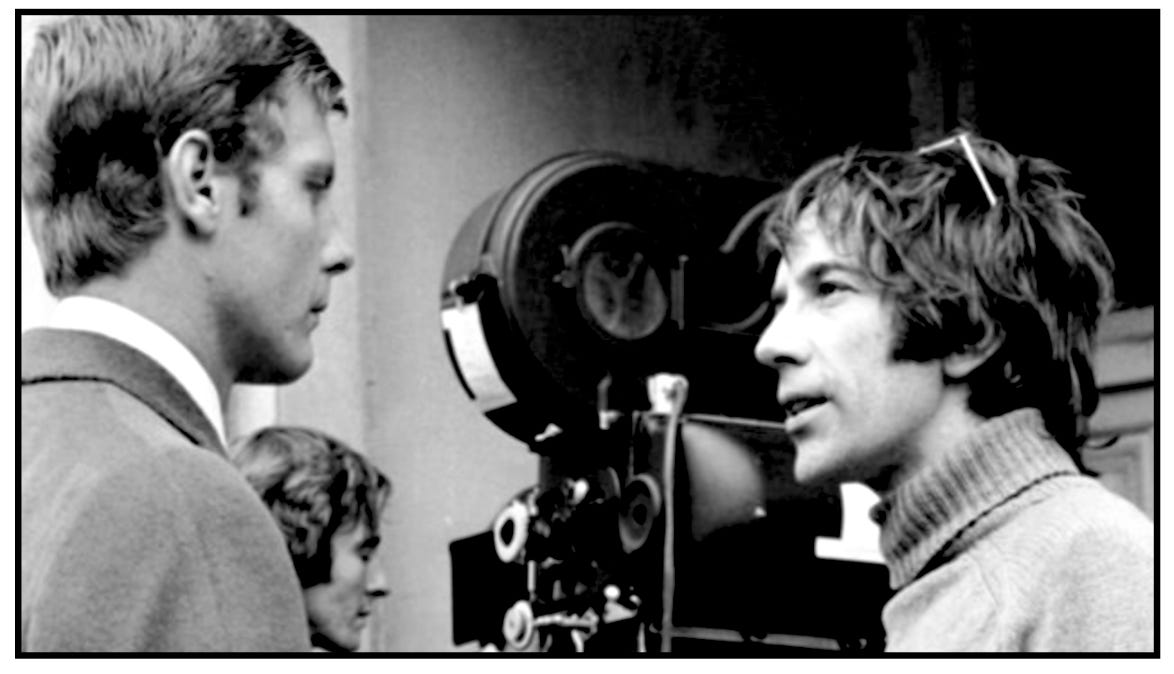

JF: Why did Donald Cammell co-direct the film with Nicolas Roeg?

SU: Donald had known Nic Roeg for many years. In the 1950s, when Donald still had his studio in Chelsea, he had painted the portrait of Nic Roeg’s first wife, actress Susan Stephen. Donald’s brother David had known Nic Roeg since the Fifties, too. When the opportunity to make Performance presented itself, Donald had to solve two problems, how to sell himself as a first-time director, and find a cinematographer. He and David already knew Nic Roeg, who by that time had shot some major films and was interested in becoming a director, so Donald proposed they direct the film together.

JF: Donald Cammell began his career as painter. How do you think his background influenced Performance?

SU: Like the late great David Lynch, who was also a painter before he became a filmmaker, Donald Cammell had keen instincts as an artist, a great visual eye, and he had shown prodigious artistic skills as a child. Performance merges the worlds of art and crime, two sides of the same coin, creation and destruction.

JF: What were some of Donald Cammell’s other influences on Performance?

SU: Several films, some more important than others. I think Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), an exploration by Bergman on the theme of the vampiric artist, was certainly an influence. I think it more influential than, say, Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963), frequently cited by some critics as an influence due to its use of the Kammerspiel or “chamber play,” a drama set in one location with only a few characters. But so is Bergman’s Persona.

Bergman’s film is more experimental in style, and explores issues essential to Performance, such as identity and insanity, for instance. (“The only performance that makes it, that really makes it, that makes it all the way, is the one that achieves madness.”)

But I believe it was John Boorman’s Point Blank, which opened in theaters in London’s West End during the last week of December 1967, that was the major and immediate influence on Performance.

Donald Cammell was so impressed by Point Blank that he took several members of the cast and crew to see it, and he saw the film repeatedly. Point Blank’s influence can readily be seen in Performance, for instance, in the way Harry Flowers and his fellow gangsters are depicted as businessmen rather than stereotypical thugs.

There is a strong homoerotic tension between the two male leads in Point Blank, just as there is in Performance. There are many other connections between the two films. Interested readers will have to read our book. I should point out that we’re not the only critics who recognized the connection between Point Blank and Performance. In his book, Dreams and Dead Ends (1977) film scholar Jack Shadoian astutely pointed out the indebtedness films such as Mike Hodge’s Get Carter (1971) and Performance owed to Point Blank—even without knowing first-hand the extent to which Cammell admired Boorman’s film—and his chapter on Point Blank is one of the finest pieces ever written of the subject.

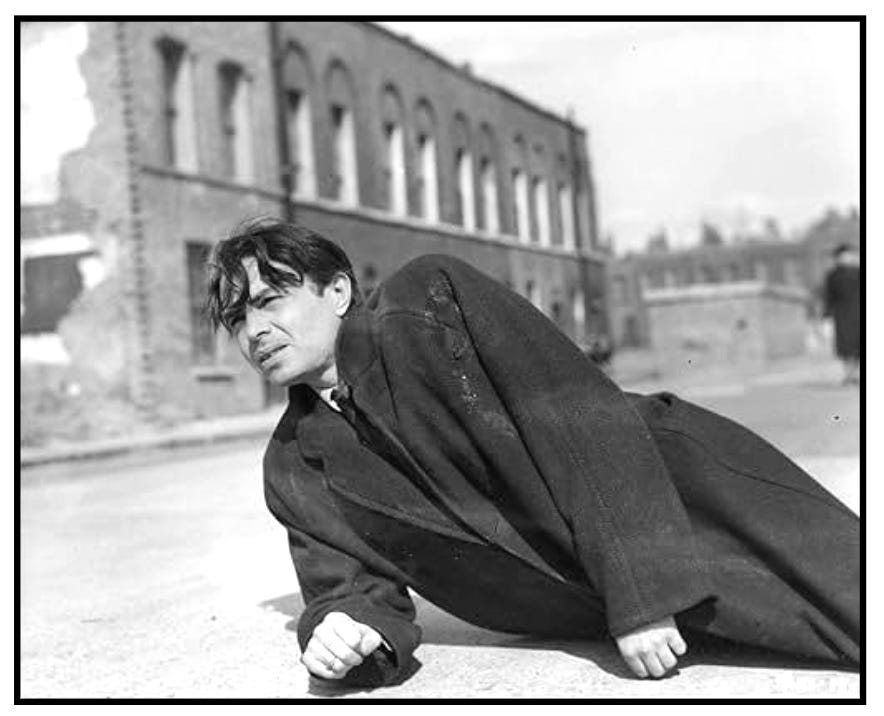

I should also mention that Performance contains a brief clip from Carol Reed’s classic Odd Man Out (1947), a film that Donald Cammell once referred to during an interview as the “secret movie” within Performance, a flash cut inserted during the sequence when Chas murders Joey. Rebecca and I discuss the connection between Odd Man Out and Performance at length in our book. Suffice it to say that Odd Man Out contains a link between death and transcendence that appealed to Donald Cammell emotionally and intellectually.

Performance is a film that moves from a mundane or desacralized existence to a “higher,” transcendent state. It begins realistically and moves toward allegory.

I should also mention that in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950), the poet-martyr Orpheus is whisked off to Death’s kingdom in a Rolls-Royce.

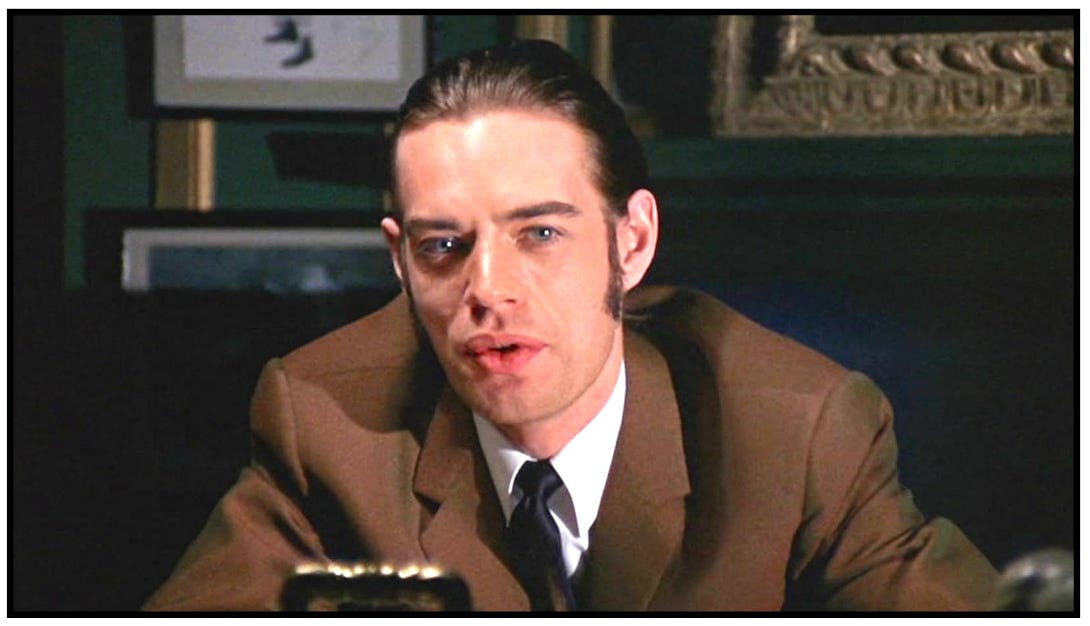

JF: How would you describe James Fox’s character Chas in the film? How does the title Performance relate to his character?

SU: Chas is a “performer,” a gangster who carries out or performs, “executes” if you will, the orders from his boss. He is also a performer in another way, a person who dons disguises and takes on a fictional self as is necessary to suit the demands of any particular occasion. It so happens that once he meets Turner, he takes on a disguise that he hopes will save his life.

The twist is that Turner happens to be a figure of the vampiric artist, stealing from another’s personal struggle or agon to use the material to transform into his art. Remember what Pherber tells Chas: Turner is “stuck.” Turner, too, is a performer. He is a “pop star” after all.

JF: Harry Flowers is also an interesting character in the film. Is he based on the British gangsters of that time like The Krays?

SU: The Kray twins were arrested and jailed in May 1968 shortly before Performance began filming, so they were very much in the news at the time the film was in the pre-production phase. One of the actors, John Bindon, who plays Moody, apparently had some sort of underworld connections.

Johnny Shannon, who plays Harry Flowers, was not connected to the Krays, although his character may have been loosely inspired by Ronnie Kray. Shannon had had some success as a boxer, and helped James Fox prepare for his role by arranging sparring sessions at a London gymnasium. He also helped him with his accent.

Interestingly enough, Johnny Shannon went on to have an acting career after Performance.

Perhaps most important, the “dialogue coach and technical advisor” on Performance, “chat artist” David Litvinoff, definitely had underworld connections and was more than a mere acquaintance of the Kray twins. It was Litvinoff, for instance, who arranged for James Fox to meet with Ronnie Kray, who was then in prison.

JF: The “Memo From Turner” sequence has often been called the first music video. How did this sequence come about? Could you break down the influences and symbols used in it?

SU: I think Richard Lester might question the notion that “Memo From Turner” was the first music video. And rightly so, since his huge commercial hit starring the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night (1964), was the film that had figured out a form for rock music.

Several sequences in A Hard Day’s Night could be considered music videos. Think, for instance, of the sequence early on in the film set in the train’s baggage car showing the group sitting around a table playing cards. “I Should Have Known Better” begins to play on the soundtrack. Then, there is a jump cut to the band sitting around the table, but they are now playing their instruments. There is then another jump cut showing the band sitting at the table once again playing cards. The use of sound in this sequence is vitally important, because Lester had demonstrated how easily you can move between the diegetic and nondiegetic use of sound (in this case, music that occurs within the scene as opposed to music which is overlaid on the scene).

The “Memo From Turner” sequence exploits this freedom of movement on the soundtrack. The song begins to play on the radio, while the characters repeat or quote lines from earlier in the film, creating a sort of disorienting “echo” effect. When “Memo From Turner” comes on the radio (nondiegetic sound), Turner/Jagger orders the radio to be turned up, a line spoken earlier in the film by Harry Flowers. When Turner/Jagger begins to sing, the sound becomes diegetic.

The use of sound here is playful but disorienting, made more so by Turner/Jagger’s multiple guises, appearing alternately as a Fifties rebel, then as a Sixties rebel.

“Memo From Turner” is blues rock, with Ry Cooder’s slide guitar invoking a favored Rolling Stones musician, Elmore James. The lyrics of “Memo From Turner” came from suggestions by Donald Cammell, who according to Mick Jagger wanted them “dirty.” They are as far from conventional pop song lyrics as you can imagine. I should add that the lyrics were written rather quickly because the “Memo From Turner” sequence was a late addition to Performance.

If the happy-go-lucky Beatles of A Hard Day’s Night were a representation of the counterculture’s best image of itself, Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones were the counterculture’s dark double. Remember that Woodstock was followed almost immediately the same year by the debacle at Altamont.

JF: In your book, you talk about the meaning of the “final catastrophe” near the end of the film. Could you discuss the concepts of the mnemonic self and transmigration?

SU: As you say, we discuss the conclusion of Performance at length in our book. Transmigration is the passing of the soul at death into another mortal body. The mnemonic self is the one composed of our own highly personal, specific, and individual memories. (Mnemonic devices are the aids we use to assist our memories.) Memory, of course, contributes to our sense of self, the self-identity we have as we move through time.

The “final catastrophe” we are referring to is what we are to understand happens at the film’s violent conclusion. What happens? The bullet fires: we follow its path through Turner’s brain; the mirror shatters and we emerge on “the other side,” outside Turner’s house. Whose mnemonic self are we to imagine remains after Chas fires the bullet? Turner’s body—not Turner’s self—is revealed to be stuffed in a closet downstairs. But where is Turner? Near the end, he is shown in the white Rolls Royce sitting next to Harry Flowers. But what’s happened to Chas? That’s the final catastrophe we are talking about, with its deliberately elliptical editing.

JF: Performance is famous for its ending. How should viewers interpret it?

SU: Viewers should track down a copy of Jorge Luis Borges’ story, “The Enigma of Edward Fitzgerald,” in which Borges’s subject is the English poet Edward Fitzgerald, most famous for his 1859 translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. This story is included in the book from which Turner reads, Jorge Luis Borges’s A Personal Anthology (UK Edition 1968). It follows the story, “The South,” the story Turner is reading in the kitchen scene. I think reading this story will help the viewer understand the enigmatic note Rosebloom leaves for Lucy near the film’s conclusion, “Gone to Persia.” Briefly, Borges tells us that Edward Fitzgerald’s encounter with the poetry of Omar Khayyám was so powerful as to convince Fitzgerald that he was not merely a translator of the Persian poet’s works, but that he was Omar Khayyám in a previous life. Borges suggests that Omar Khayyám believed in the doctrine of transmigration, which we discussed just a moment ago.

JF: After the film originally finished postproduction, Warner Brothers was unhappy with it. Why?

SU: The short answer is sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Warner Brothers executives hated it.

Reports on the official account say that it was perceived to be a “dirty” movie, filled with sleazy sex and extreme violence. It featured the use of drugs and hinted at homosexual behavior. Nic Roeg recalled after the screening someone remarked, “even the bath water is dirty.” But I would add, my own theory—just that—is no one understood the ending, either.

JF: How did Frank Mazzola get involved in the re-editing of the film? How significant were his contributions to the final recut of the film? Since you got to know Frank Mazzola well after you interviewed him for your book, what was he like as a person? Why didn’t Mazzola get an editing credit on the film?

SU: At the time Frank met Donald Cammell, he was working as the editor on a western being produced by Joseph E. Levine titled Macho Callahan, starring David Janssen and Jean Seberg. Although the film was being shot in Mexico, Frank had requested that he be able to work on the film in his preferred set of editing offices at the old United Artists studio located on the corner of Formosa Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood (long known as the Samuel Goldwyn Studio before it became Warner Brothers Hollywood).

He got word there was a British director in town looking for an editor to help him recut a film that Warner Brothers hoped to release, assuming the recut met with approval. And so, he met with Donald, and they discussed what they might do with Performance. He liked Donald’s ideas and decided he wanted to work on the film, so he turned Macho Callahan over to his assistant editor and moved his editing office next door, where he and Donald worked on Performance. Serendipitously, many years later and after Cammell’s death, this same editing office was where he would recut Wild Side.

Frank told me that when he first screened Performance, his initial impression was that film played “too slow,” it just plodded along, without energy. He said the first half played just like the second half. Nothing like the version we have now.

He told me several times that the majority of his work on Performance was on the first half. The delirious montage in the opening shots, the flash cut to Mick Jagger spray-painting the wall, all of that and more was done by Frank. He also made a few cuts in the second half, for example, cutting in the shot of Turner smashing the mirror with the pistol in order to “punctuate” the conclusion of the “Memo From Turner” sequence.

What I think he was most proud of was the fact that he and Donald did all that recutting in very little time, fewer than eight weeks. Warner Brothers was pushing them the entire time to get it finished as fast as they could. And he helped make the film releasable.

Frank was a friendly, fascinating guy, and I learned a lot from him. He’d grown up in Hollywood, had spent his entire life there. He had lots of stories about the “old” Hollywood, about his adventures as an editor; one of his mentors had been Aram Avakian.

He told me about working on Rebel Without a Cause (1955), about his friendship with James Dean and with Nicholas Ray. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of Hollywood history. One time we had lunch in the commissary at Warner Brothers Hollywood, and after lunch he told us the story behind every picture hanging on the commissary walls, the context, where, when, everything.

As for why he didn’t get editing credit on Performance, I know Donald tried to get him credit. He showed me the letter Donald wrote to him explaining why he was unable to get screen credit for him. As I recall, it was something about a union issue, since the film already had contracted, credited editors, and Frank’s work wasn’t considered substantial enough. We had many good times with Frank and his wife Catherine. He was a wonderful person and a good friend.

JF: When the final cut of Performance was finally released to theaters, what was the public’s reaction to it? How did critics review it? Did it do well at the box office?

SU: The film was attacked using the rhetoric of moral outrage. Richard Schickel, in Time magazine, said it was “the most disgusting” film he’d ever seen as a professional reviewer, and said it was “completely worthless.” For John Simon, in The New York Times, it was “sleazy.” The hip journal of the era, Rolling Stone, reproduced a still from Performance, prominently featuring Mick Jagger, on the cover of its 3 September 1970 issue, but reviewer Michael Goodwin gave it an ambivalent reception, saying it was “stunning…in the sense of a body blow” and concluded, “Performance is a very ugly film.”

Even before its release in the UK, the film made headlines. A British underground newspaper called It gave Performance a front-page splash with the headline, “Jagger’s Sadist Movie Finally Released,” and proclaimed it “A Heavy Evil Film, Don’t See It On Acid.”

As you might imagine, it didn’t do especially well at the box office. Now, of course, it is considered by many to be one of the greatest films ever made. You needn’t ask me if I disagree.

(Part Two of my interview with Dr. Sam Umland focuses on Donald Cammell’s personal life and the films he made after Performance. Look for it here soon).

An outstanding interview with Dr Umland a foremost film scholar and author. Great insight into the film Performance and intriguing behind the scenes detail. This is a film that requires multiple viewings due to the multiple layers Cammell laid down both in thought and vision as well as production and post production. If you are into really indepth intelligent discussion on this particular movie get and read Umland's on Donald Cammell-A Life On The Wild Side. I believe if I were teaching a modern film class this would be on the reading syllabus not to mention a class screening. Well done gentlemen- disclaimer I've known these fellows for 40 years

Waa JD Vance in it?